REENA SAINI KALLAT

“Ever since the Cognitive Revolution, Sapiens have been living in a dual reality. On the one hand, the objective reality of rivers, trees and lions; and on the other hand, the imagined reality of gods, nations and corporations. As time went by, the imagined reality became ever more powerful, so that today the very survival of rivers, trees and lions depends on the grace of imagined entities such as the United States and Google.”

- Yuval Noah Harari: Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, 2011.

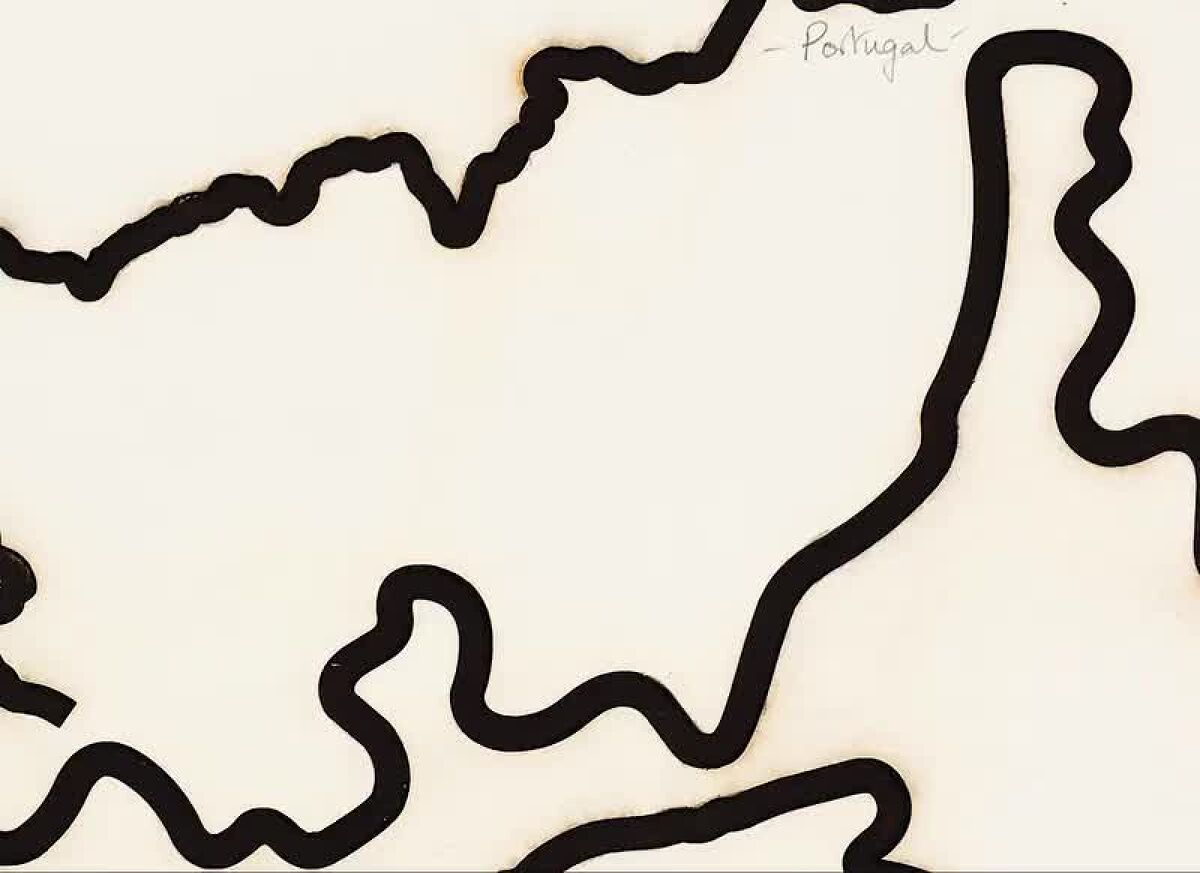

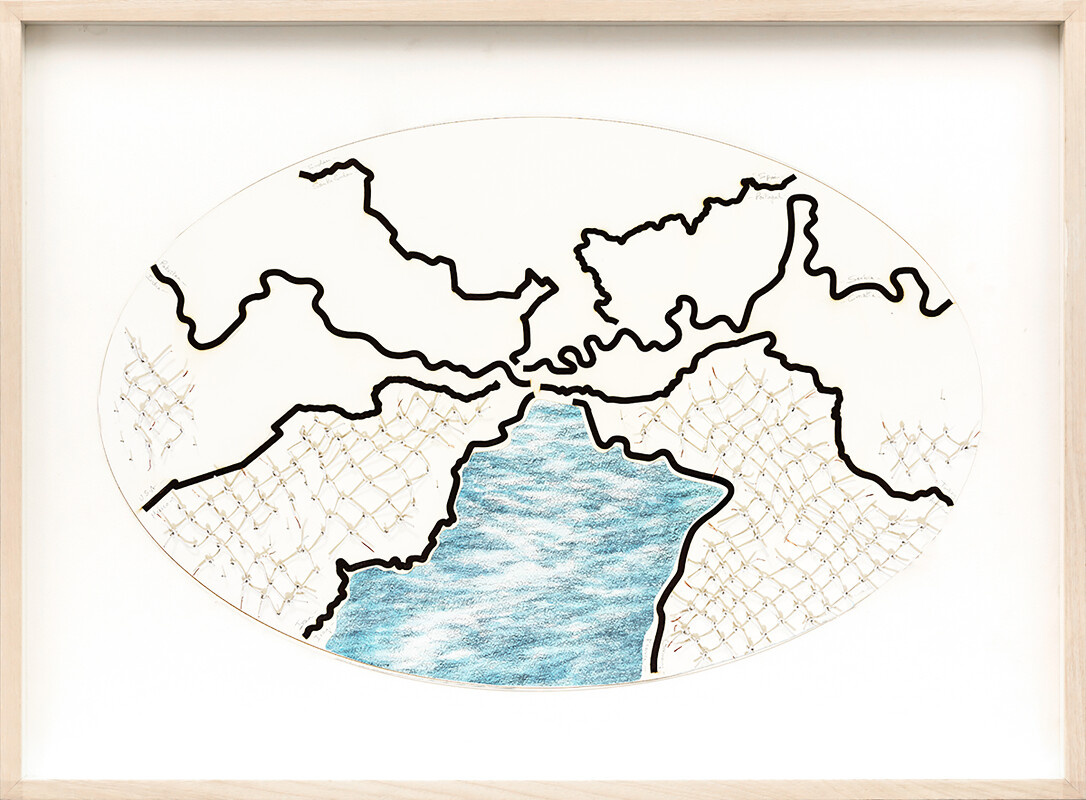

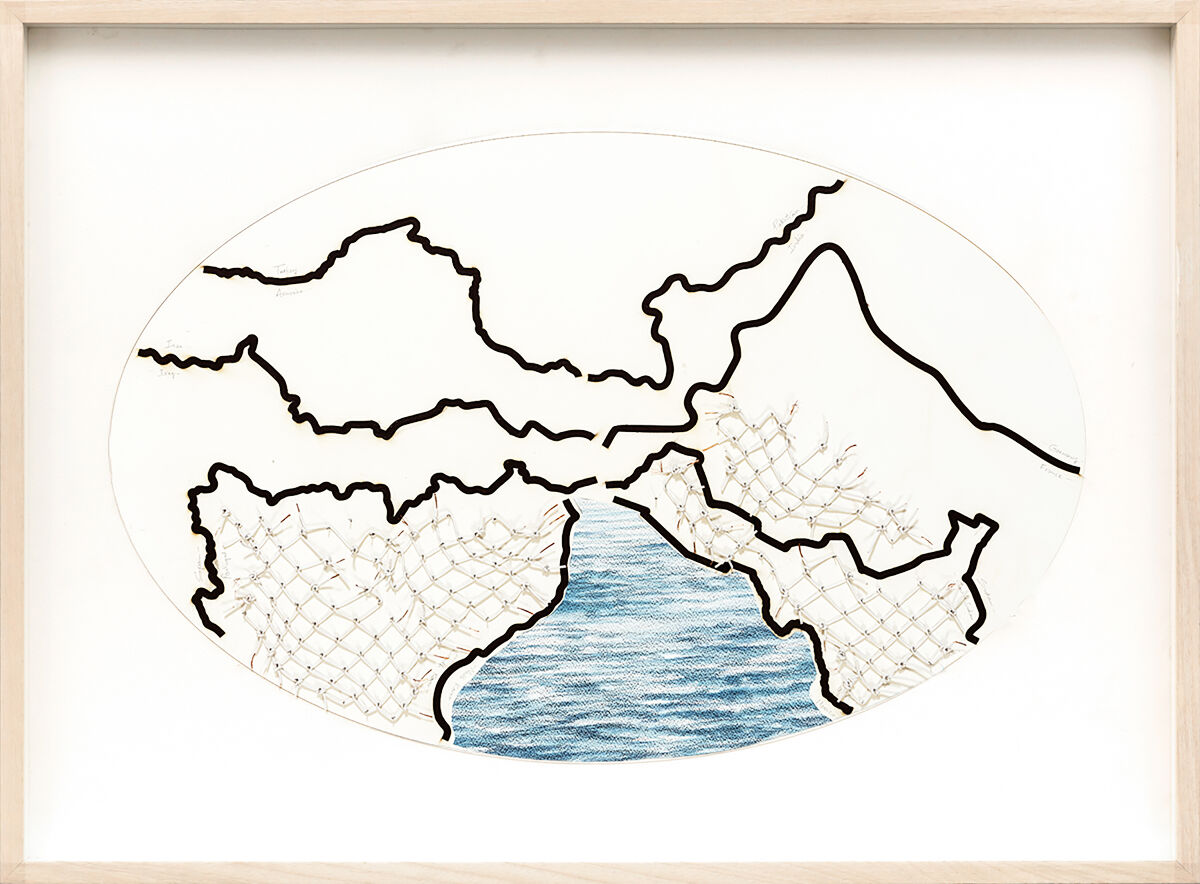

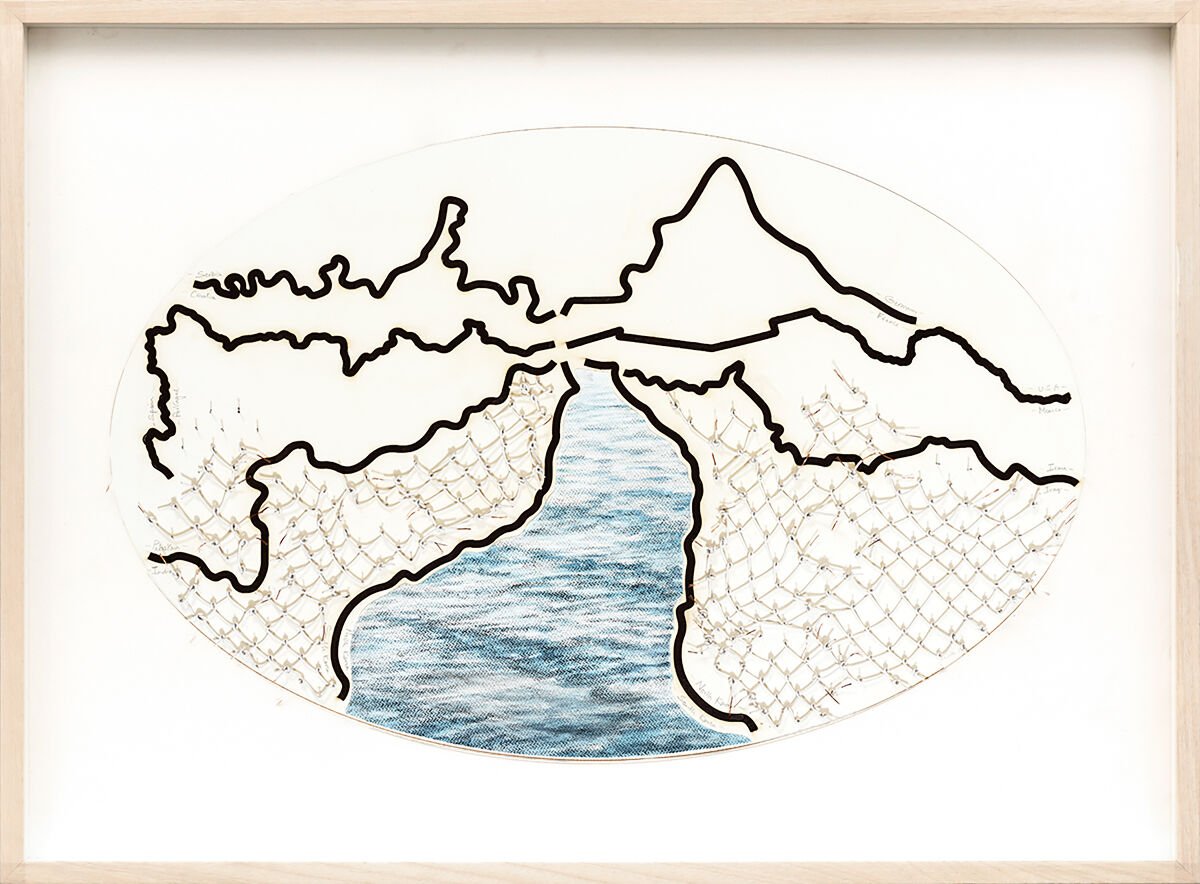

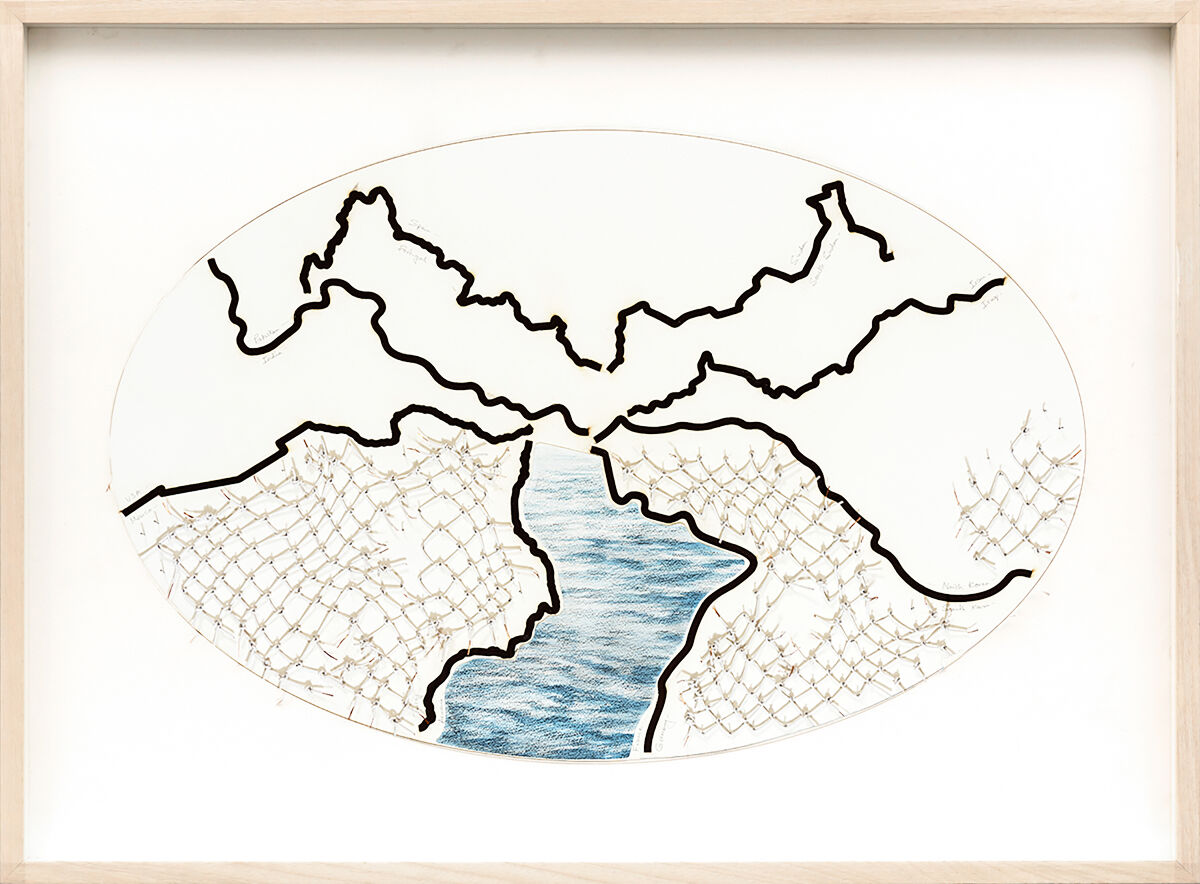

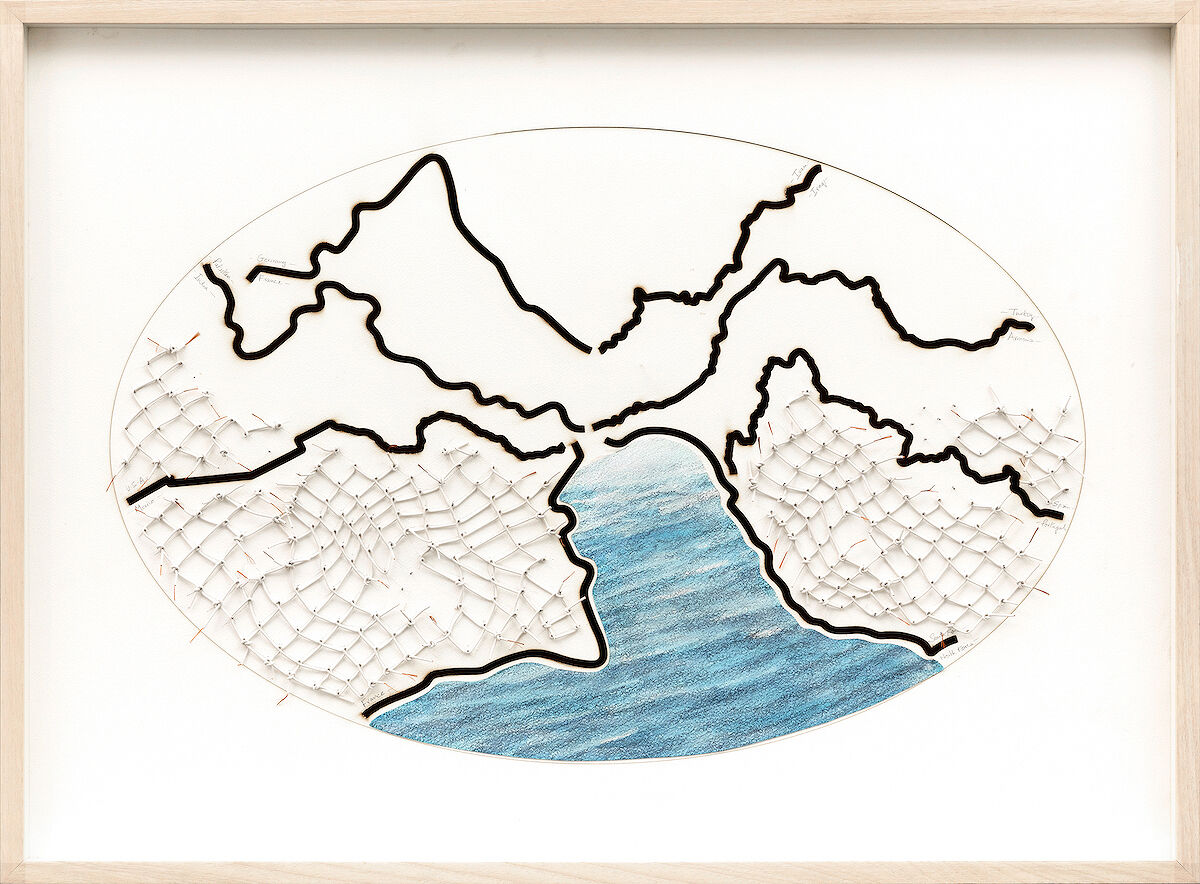

For the past several years, Reena Saini Kallat has been exploring the imagined divisions of the world into separate nation-states. Her own family history overlaps with the partition of the subcontinent into the two entities of India and Pakistan in 1947, an action which resulted in a mass migration with disastrous consequences for many people. It is well known that the man who decided the physical line that would separate the two countries did so from an office in London, having never visited the sub-continent itself, and in great haste, no less. Such divisions were a common occurrence in the aftermath of the Second World War and the dissolution of the colonial structures, but their repercussions continue to be felt acutely today. One could posit that some seventy years later these divisions have acquired an increasing irrelevance due to advances in communication technologies, yet we see a rise in political ideologies that defend these divisions more strongly than ever.Kallat’s approach to this subject is both poetic and speculative. In previous works, she has envisioned both flora and fauna that represent the hybridized state, fusing together the official symbols of two nations’ identities into chimerical new wholes. Other works have illustrated constitutional texts on which national tenets have been defined in languages which transcend cultural and administrative contexts.

IN THE STUDIO

with

Reena Saini Kallat

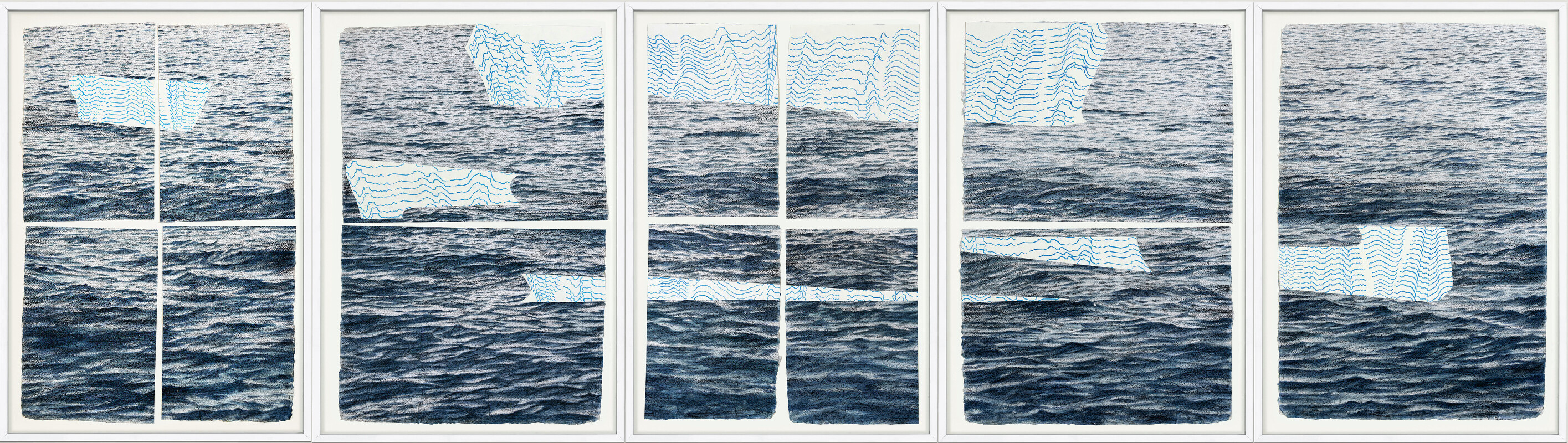

Reena Saini Kallat’s (b. 1973, Delhi, India) practice spanning drawing, photography, sculpture and video is concerned with ideas that hold each other in tension—barriers in a world of mobility, porosity in sites of fissure, memorialisation in the aftermath of amnesia, and the promise and illegibility of national legal documents. Kallat’s interest in political and social borders—and their violent cleaving through the land, people and nature—resonates with the continuing aftershocks of the Partition in India, which her family experienced. Kallat has researched various histories of migration, the plunder of shared natural resources for national gain, and archives of disappeared people. The figure of the hybrid has come to hold symbolic potential in Kallat’s practice, as a truant against dividing lines and divisive national narratives. That barriers give way and can be subverted, is an idea that is pronounced in Kallat’s work using electric cables twisted to resemble barbed wire. She uses the paradox of the existence of technology for the free flow of information and restriction on movement to suggest that total isolation is not possible. Where there is contact there is exchange and fusion.

Memory is an important site of investigation, to regard not only what we choose to remember but also how we think of the past. Kallat is particularly interested in foundational legal texts, and the words therein that give nations legitimacy. In them, she highlights universal principles of freedom and equality, as well as their tendency to create an enemy for their own sustenance. Kallat’s examinations highlight the limits of perception, of both individuals and societies, to reveal blind spots that might allow the clearing of a shared vision.